Locked into Luxury

When it was built, Boston's Charles Street Jail housed some of the worst offenders in the country. But, today, after undergoing an incredible, 2-year transformation, the building houses some of the country's elite by serving as a lavish hotel. Once functioning as a building in which no one wanted to spend the night, it's now a building in which people pay to stay.

An admirable example of prison architecture for the second half of the 19th century, time eventually took its toll on the building. In the 1970s, the building was declared unsafe for its prisoners due to poor living conditions. The prison closed, and its prisoners were relocated to a new building. About 20 years later, Massachusetts General Hospital acquired the outdated property and began asking for proposals about how the building could be repurposed. One of the proposal requirements from the hospital: Certain elements of the jail should be preserved. "It was felt that the building was best suited to a hotel, and that it would also fulfill some of the needs of a major urban hospital," says Gary Johnson, associate principal at Cambridge, MA-based Cambridge Seven Associates Inc. So, Carpenter & Co. Inc. (also located in Cambridge, MA) was selected as the developer in 2001, and it began the process of turning the old jail into a $75 million, four-star hotel. The conversion from jail to luxury hotel was complete in 2 years, and the hotel opened for guests in October 2007.

"It was such a fantastic building in such an important location in Boston," says Darren Messina, vice president and director of development at Carpenter & Co. Inc. "We just really wanted to commit to adaptive reuse as much as possible." Messina and his team coordinated with the Massachusetts Historical Commission, the Boston Landmarks Commission, the National Park Service, and the Boston Redevelopment Authority. And, because the building was designated as a national landmark, it was decided that all decisions would be made to preserve this status. "The project was also eligible for historic tax credits at the federal and state levels," explains Johnson. "By maintaining the historical integrity, those credits could be realized."

Overcoming Obstacles

With a project this monumental, there were bound to be some challenges—but none that a good project team couldn't overcome. Coordination and teamwork helped keep the project on target, which wasn't easy, considering some of the tasks that needed to be completed. The construction team was dealing with selective demolition, removal, and salvage, says Mike Cheney, project manager, Suffolk Construction Co. Inc., Boston. "In one section of the jail, everything that was demolished needed to be reused—from bricks to jail-cell bars. There was a major effort to document existing conditions to reincorporate all salvaged materials into the final product."

In addition to the difficulties that often come along with historic preservation, the hotel is also adjacent to two of Boston's largest and busiest hospitals, making the project even more challenging. Some of the hotel's utility lines were shared with these buildings, as well as a lay-down area for construction materials, explains Cheney. "The team partnered and maintained a solid working relationship with the hospitals' facilities staffs, coordinating construction activities, material deliveries, and utility shutdowns. We held formal weekly meetings with the staff at each hospital to provide construction updates and work out any issues that construction activity could cause to hospital operations."

The building also sits on two parcels of land—both of which are owned by different city agencies. The project team was able to efficiently navigate the permitting process, which helped keep the project on track. With the new construction and renovation work being done at the same time, two projects were being managed at once. "It was essentially two projects coming together at the end to form one spectacular hotel," says Cheney.

Another big challenge, from Johnson's point of view: "Holding up the roof of the wings of the old jail while the jail cells were removed." He explains that the building was built so that the jail cells, which were located in the center of each wing, also supported the roof. Removing the cells meant that the roof needed to be temporarily supported while the old cells came down, and then had to be permanently supported when new floors and columns were placed within the building.

Preserving the Past

Historical requirements from the National Park Service mandated that as many of the original materials be reused as possible. By hand, laborers physically sorted through 100,000 bricks from demolition to pick out the ones that could be reused. The bricks selected for reuse were cleaned and stored for 1 year until they were ready to be used in final construction.

To ensure historical accuracy of the project, the team used original architectural drawings. True to its previous form, the hotel consists of a 90-foot, octagonal central atrium that features four circular wood ocular windows, historic catwalks, and four radiating wings, each with 34-foot arched windows that imitate details from the past. The renovation also brought back the building's cupola, which had been removed in the late 1940s. The granite exterior of the building was restored and remains largely unchanged, with new slate roofing.

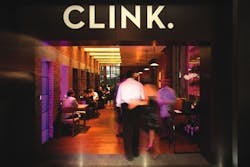

Inside, jail cells were preserved and are now held within the hotel's restaurants/bars (aptly named "Clink," "Alibi," and "Scampo," which is Italian for "escape"). Exposed brick walls and a wrought-iron chandelier complement the lobby and hold true to historic materials. What used to be the prisoners' indoor recreation area is now the main lobby, complete with a reception desk made of ebonized wood with lacquered, stenciled patterns that are reminiscent of 1850s embroidery work. Surrounding the main lobby are the catwalks that were once used to move prisoners to and from their cells.

A new, 16-story guestroom tower features glass and iron-spot brick. With these distinct design features in the new section of the hotel, there's an obvious separation between old and new.

The biggest success of the project from Johnson's standpoint has been watching the building come alive once again. "For the first time in 160 years, its doors were opened to the public—not as a place of sorrow, but as a place of joy and true hospitality," he explains. "It has become a must-see in Boston—not just because of its past, but because it's now alive with positive energy and transformation. The city has gained not just a new hotel, but a new vibrancy in a location that has always lacked ‘sparkle.' "

Judges' Comments "This building clearly indicates the potential that this country has for some of its aging infrastructure. Through careful thought, adaptive reuses can be found for almost any type of building." |

Leah B. Garris ([email protected]) is managing editor at Buildings magazine.