The Easy Road to Roof Sustainability: Part 1

Building owners and managers are inundated with advertisements for the very best roof maintenance or repair programs. The advertisements are clever, and assure the reader that a durable, inexpensive quick fix is at hand.

They tend to follow fads. Very often, they are offered by second-tier material producers; those that are quicker to react to trends and recognize opportunities. Large producers have high-capacity production facilities that are difficult to convert to new products. In fact, one trend has been to acquire these more nimble competitors when they seem to have hit upon a winner.

Quick Fixes for Your Building

As with many other columns in this series, we will address fixes for commercial roof systems in the following order:

- General conditions, typical of all roof systems, but slanted toward bituminous systems since these were dominant in the 1960s and ’70s.

- Polymer-modified bituminous roof conditions, as they are similar in behavior.

- Single-ply systems, which are split into the two major categories – those that are weldable and those that are not.

- Structural, standing seam roofs.

- Spray-in-place polyurethane foam.

The conventional built-up roof system can be identified as having one of three surfaces: flood coat of asphalt or pitch, into which gravel or slag has been embedded; mineral-granule surfacing (cap sheets); or smooth-surfaced roofs.

The “jiffy-fix roofing company” representative offers you a liquid product that is sprayed over the existing system, with little concern for the existing roof’s condition. In many cases, this firm does not have the time or talent to analyze what the real problems are, so a “band-aid” approach is taken. The products offered have ranged from “resaturants” that were supposed to rejuvenate the old roofing felts, to asphalt cut-backs, to the current vogue of water-based coatings (generally white acrylics). Claims generally discuss extensibility (it can stretch 1,400 percent), lower roof temperatures, and easy clean-up with soap and water.

The smarter, middle-tier manufacturer will realize that roof maintenance decisions require much more thought and study. First, why is the owner inquiring about the product or service? The most likely answer is roof leaks. Fixing the leak is obvious, but the issues are:

- Why is the roof leaking? Punctures and surface defects are easy to spot. But many times, leaks have nothing to do with the roof membrane. In extreme cases, the entire roof system has been replaced and the leaks are still there. HVAC units are frequent culprits, as are bad walls, condensation issues, etc.

- Is the roof system sustainable? If the roof is splitting, no cosmetic patch is going to hold it together. The base cause of the splits must first be identified. It may be a poorly attached roof system, allowing thermal stresses to accumulate. In extreme cases, roof membranes have fluttered or lifted in high winds, resulting in fatigue failure. Until you stabilize the substrate, no patch will hold.

- How much damage has occurred? This would include wet thermal insulation, rusted or spalled roof decks, and rotted wood nailers. Is the roof membrane being attacked by chemicals or hot exhaust gasses? Are components delaminated allowing shear forces to accumulate?

- What is the building owner’s agenda? Just patch to get another year, a major capital improvement program including upgraded thermal insulation and drainage, or what?

The May 2002 issue of Roofing News covered gathering information for an intelligent re-roofing decision. It suggested incorporating moisture surveys and hiring of qualified roof consultants.

Some middle-tier material suppliers offer such services as part of their marketing program. In a few cases, the field service people are very well-trained and will provide thoughtful recommendations. Other owners may feel an independent roof consultant is a better route to go, separating analysis from product specification.

For the bituminous case, let’s take a low-slope, gravel-surfaced roof, installed in the mid-’70s. The roof has some blisters, eroded areas, the flashings have torn in some areas, there are punctures around the HVAC units, and the embedded gravel-stops have many small splits in the stripping plies – right over the laps of the gravel-stop metal. The pitch pockets (open-bottom pans that hold sealant) need to be refilled. There is just one layer of roof insulation, and some of it feels wet. Some felt edges are curled up, deteriorating where exposed to UV, oxygen, and moisture.

The consultant or in-house expert would first decide if this system is worth saving. Let’s say “yes” for the purposes of this article. You decide to remove the few wet areas and replace the insulation in kind. The deck was in good condition, but the flashings really need to be replaced. The gravel-stop metal is in good condition, but you elect to peel away all the felt stripping plies (and previous patches) and reattach the metal where fasteners have backed out.

Let’s discuss appropriate repair materials. As far as the surfacing goes, you could use a high-pressure, low-volume wet vacuum to remove the loose aggregate and dirt. Wherever you plan to make a patch, the next step is to spud (chip away adhered gravel) for about 6 inches onto the sound part of the membrane. This is critical, because if the perimeter of the patch fails, water will penetrate at once.

You now need your first repair material. This is a bituminous primer, to promote adhesion to the spudded area. The traditional material will be asphalt primer meeting ASTM D-41. It contains petroleum distillate (mineral spirits) and asphalt. It is brushed thinly onto the surface where the patch will be tied in (the spudded area). It can be purchased from a roofing materials distributor, but unfortunately may be available in only 5-gallon pails – even if only a teacup-full is needed. If this is the case, purchase 1 gallon of non-fibrated roof coating from the local hardware store, and a pint of mineral spirits (paint thinner). Mix a pint of coating and pint of mineral spirits together, and you have the needed primer.

Another high-tech alternative is primer in a spray can. You are paying for the can and propellant, but it is convenient for very small projects.

You may be asking, “Isn’t there a possibility that the roof has coal-tar instead of asphalt?” Good point. Some experts can smell the difference by burning or breaking a bead of bitumen from the roof. Drop a bead of bitumen in some petroleum spirits or gasoline and swirl it around. If it quickly turns brown and starts to dissolve, it is asphalt. If the lump just lays there, and perhaps after a few hours takes on a yellow/green cast but is still clear, it is coal-tar pitch. In this case, you may wish to use a pitch-based primer, which will be harder to locate – but asphalt primer should not be used.

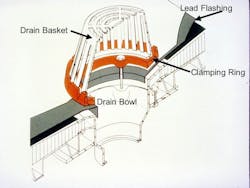

If the stripping plies that waterproof the metal flashing around the roof drains are distressed, spud away the remaining aggregate and flood coat, and remove the stripping plies. These plies are clamped into the drain bowl, so after removing the strainer, unbolt the clamping ring very gently. Those old bolts may want to break off instead of backing out, and suddenly you have an all-day project. The bottom side of the metal clamping ring should be wire-brushed to remove grit.

A spud bar or straight-claw hammer will do to remove the old flashing plies and to remove the flood coat and aggregate for 18 inches on each side of the drain, but wear eye protection. Again, prime. Now install new bituminous felts to seal the edges of the lead drain flashing. These can be conventional glass-ply roofing felts (usually sold in a 540-square-foot roll – five squares). Roof mastic (a mixture of mineral spirits, asphalt, mineral filler, and fiber) is a general-purpose repair compound. Any lumberyard or hardware store will carry this. One-gallon pails are pretty small for this work. A 3-gallon pail is available from some distributors, and is easier to lug around than the conventional 5-gallon pail. A trowel is also needed. For the record, asbestos fibers are still being used and make an excellent repair material for patches, as well as for flashings. Asbestos-containing mastics are no longer regulated by OSHA nor EPA, since the fibers are encapsulated. If you wish to avoid asbestos, asbestos-free materials are also available.

A higher-tech alternative patching system would be to use a roll of modified-bituminous (MB) material (see illustration 30-1). Cut a center hole in a 36- by 36-inch sheet (or 1- by 1-meter), and install by torching the MB material to the lead flashing, directing the heat to the back of the MB, not the lead. You also could embed the MB sheet into a bed of a recommended mastic. Round the corners of the MB patch before installing. This is reportedly a reliable way of preventing the corners from curling up. Reinstall the clamping ring, making sure all the bolts are present, and torque (much as you would when replacing a wheel after a flat tire) one side and then the other to get uniform clamping pressure. If the roof had an aggregate surface, you could now use mastic to coat the exposed patching material and re-embed aggregate that has been swept up from the surrounding area to match the rest of the roof.

Gravel-stop metal is repaired in similar fashion. Prime and re-strip with two plies of glass-fiber roofing felt. If you have lots and lots of metal to re-strip, you can use hot asphalt instead of mastic. You could also consider torching a modified-bituminous material, but the fire risk is high with combustible wood nailers and roof insulation edges just below the metal (see illustration 30-2 of embedded gravel stop installation).

For just an occasional split at the end-lap of the metal, woven glass mesh is very suitable. It generally is 8 or 10 threads to the inch, treated with bitumen or resin. Some producers provide a distinctive color such as yellow or bright green, but the only advantage to the bright color is that you can see it in order to make sure it is completely covered with mastic when patching. Stripping plies may be 6-inches wide, followed by an 8- to 9-inch second ply, so that the back edges of the plies do not coincide. This technique is called “feathering.”

Wall and curb flashings used to be patched with asphalt mastic and asbestos roofing felts. When asbestos roll goods were withdrawn from the marketplace, the glass-fiber replacements were considered inferior. Fortunately, modified-bituminous materials are available, generally with either granule-surfacing or metal foil for UV protection. Torch application is most convenient for MB flashings. Compatible mastic can also be used, but not for the foil-surfaced sheets as the solvent cannot escape. Hot asphalt has been used, but it is difficult to put the mop on the wall, and back-mopping and flopping is labor intensive.

Because flashing materials are heavy and the vertical configuration results in gravity pull, the tops of the flashings should be mechanically fastened along the top edge (usually with capped nails or screws with stress plates). For masonry, the fasteners are driven into mortar joints, not the brick itself. The top edge of the base flashing and the fasteners are now sealed with mastic and mesh, and if a counter-flashing is available, it should extend down beyond the fasteners and stripping (see illustration 30-3).

How about just recoating the old flashing with mesh and mastic, or even acrylic mastic and coating? The answer lies in the reason we are repairing the old flashing. If it is poorly attached and diagonal wrinkles are appearing, which are fatigue-cracking, no surface treatment is going to last very long. However, for an occasional puncture or single crack, bridging with such materials will last for a couple of years.

You may be wondering, “Do we want to replace the flood coat and aggregate from the bare areas?” It really depends upon the nature of the original felts. Organic felts are like blotting paper, and must be protected by the flood coat of bitumen (or mastic for small areas) and aggregate. But in the ’70s, asbestos and glass-fiber felts were also available. Being inorganic, the flood coat is less critical. Both glass-fiber and asbestos roofing systems have been offered with no surfacing at all!

If you wish to re-embed aggregate over the entire roof, special mastics called resaturants may be used. These provide a good, sticky mastic to hold the aggregate. Resaturant producers used to claim that the material would reimpregnate the roofing felts and rejuvenate the roof membrane, but these claims were clearly exaggerations. Some consultants point out that the cost of resaturating a roof cannot be justified, since 7 to 10 gallons of material must be used, and for the same money, the entire roof assembly could be torn off and replaced with a brand new system and receive a long-term warranty as well. For small wind-scoured areas, such as near roof corners, resaturant or ordinary mastic would do fine.

Another common maintenance item for low-slope roofs is the use of “pitch-pans.” These are open-bottomed containers with horizontal flanges that rest on the roof membrane. Penetrations are brought through the roof deck and membrane, and sealed with some waterproofing pan-filler. The term “pitch-pan” goes back to the old coal-tar pitch days, when the bottom of the pan around the penetration would be stuffed with a compressible material such as crumpled paper or insulation. Hot pitch would be poured into the pan to act as a sealant. Later on, hot asphalt was substituted, but both shrink as they age, and may pull away from the pan edges or allow water to enter the roof system. Asphalt mastics have also been used and are the easiest to use when refilling a pan that is low on sealer.

High-tech materials work well here. One is an asphalt-free material introduced by the single-ply producers who did not want to contaminate their rubber or plastic systems with an asphaltic substance. This pourable sealer may be a two-component material mixed on the job, and is most practical when there are a number of pans to be refilled, since the mixed material has a short pot life and must be used within 1 hour or so. Other sealers are one-component and rely upon moisture from the air for curing. They cannot be used in great thickness because the interior of the mass would not get enough moisture to cure. In some cases, all but the upper 2 inches of the pan is filled with Portland cement or the like.

Is Fixing Worth It?

Pros: Fewer disturbances to the occupants of the building. Not terribly expensive, especially since the cost of this type of program could be spread over several years. In-house personnel can be trained to do the routine patching as needed, to keep pitch pans full with sealer, and to patch an occasional split at the gravel stop.

Cons: Such maintenance rarely qualifies for a guarantee. Even the roofing contractor cannot assure you that all leaks have been discovered and repaired.

Next month, we’ll look at MB systems and various aspects of their maintenance and materials.

Resources:

Asphalt Roofing Manufacturers Association

Roof Coatings Manufacturers Association

Roof Consultants Institute

National Roofing Contractors Association