Transforming Flush Valve Technology

When the Energy Policy Act (EPAct) was amended in 1992, mandating fixtures (especially toilets and urinals) with considerably lower water consumption, the plumbing industry was forced to make sweeping technology changes.

One fitting that has seen significant change is the flush valve. Before 1992's volume restrictions, the discharge from any flush valve adequately met the needs of its partner fixture. There were few compatibility issues because the extra (wasted) water was not a big concern. In fact, the engineers who designed the flush valves worked independently of those who designed commercial toilet bowls and urinals.

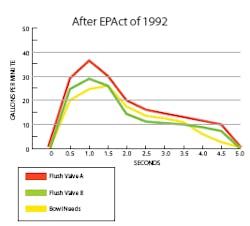

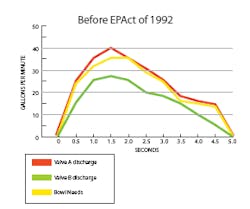

Today, the tolerances between flush valve discharge and bowl needs have shrunk to the point where fixture/fitting compatibility should be a careful consideration when specifying mated products from different sources. To illustrate, below are two graphs that show curves for flush valve discharge and bowl needs before and after the low-consumption requirements went into effect. (These illustrations chart events at specific test pressures.)

Clearly, Flush Valve B does not meet the bowl's needs at the end of its discharge cycle, so it does not restore the trap seal. Therefore, both fitting and fixture manufacturers should agree that a specified combination will perform properly at all anticipated building pressures before their selection. Simply leaving this matter to the bidder is no longer satisfactory. Of course, the simplest solution is to use fittings and fixtures from the same manufacturer, a recent trend in the green-building age.

Another notable trend is the swing toward using piston technology in flush valves. The ubiquitous diaphragm valves were discovered to vary by as much as 30 percent in discharge from the 30 psi (for which they were designed) to 80 psi. Piston valves have proved to be more predictable and vary only 6 percent (from 15 psi to 125 psi), opening their application to building environments where pressures vary this much.

Concurrently, the rise of sensor operation, a standard in most public facilities, has made "hands free" almost a code requirement. Competition between manufacturers now focuses on the energy sources used to activate the sensors and solenoid valves, and has precipitated a technology explosion. These energy sources range from hard-wired transformers (dependent on the grid) to batteries (that need changing and contribute to hazardous waste), solar power, and water power (the greenest of all) that uses the kinetic energy flowing through the valve. Manual flush valves, often value engineered into specifications to remain within the construction budget, are soon replaced with sensor-operated valves using funds from the maintenance budget because they reduce maintenance costs.

Gunnar Baldwin is senior manager of business development at Morrow, GA-based TOTO USA Inc. (www.totousa.com).