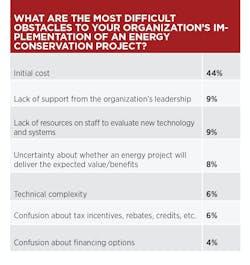

For years BUILDINGS readers have rated energy as their number No. 1 operating cost concern. And for as many years, they have also said that the No. 1 obstacle to an energy improvement project is initial cost.

In a survey of building owners and facility managers conducted in June 2013 for this report, 44% of respondents said that initial cost is the greatest obstacle to an energy retrofit. That percentage of respondents is more than four times larger than for any other hurdle to a retrofit (see table).

However, new financing vehicles are helping owners to overcome this obstacle. The goal is to use future energy savings to pay for the upfront cost of energy retrofits. When structured properly, such vehicles can generate positive cash flow from the outset. With longer terms, they can also fund deeper retrofits that supply more savings.

While it takes time and resources for building owners and lenders to navigate the financing labyrinth, the results can be well worth the effort. If your organization is wasting money on inefficient equipment, it may be able to quantify the waste and use it to finance energy improvements without paying large initial costs.

This special report looks at several emerging solutions: PACE (Property-Assessed Clean Energy), on-bill financing, ESCOs (Energy Service Companies), and managed energy services agreements (MESAs). The article also looks at the special situation of small commercial buildings under 50,000 square feet. PageBreak

PACE: A New Source Seeking to Reach Its Stride

Any shortlist of common obstacles to energy financing would include the following:

- Initial cost

- Difficulty of obtaining low, fixed interest rates

- Difficulty of obtaining long terms up to 15 or 20 years

- Recovery of the energy investment if a property is sold

PACE (Property-Assessed Clean Energy) programs are designed to jump those hurdles with ease.

The key feature that energizes the PACE concept is funding through an assessment made to the building owner’s tax bill, much like any other municipal tax assessment. The assessment provides collateral for the debt and skips around the large upfront payment of conventional financing. It can be transferred seamlessly to a new owner via the property tax. While paying the assessment nestled in the property bill, the current building owner and any future owner profit from lower utility bills made possible by the energy equipment upgrade. The assessment itself is secured by a senior lien on the property.

To enact PACE programs, states must pass enabling legislation that authorizes municipalities to place an assessment on properties as a means of repaying funds for energy efficiency or renewable energy. To date, 31 states have enabled such legislation. However, the legislation itself does not create programs, it only permits them. As a result, some states that have passed legislation do not yet have working PACE programs. Some PACE programs are too new to have yet funded a project (see map below).

This 35,000-square-foot, multitenant shopping plaza in Norwalk, CT, used PACE funding to retrofit exterior lighting with LEDs.

- $170,000 PACE assessment

- 13-year term

- Fixed 4.5% rate

- Estimated annual savings: $17,500

- Projected electricity savings: 152,000 kWh

To date, 31 states have enabled PACE legislation. The legislation itself does not create programs, it only permits them. As a result, not all enabled states have PACE programs and not all programs have funded projects.

Overcoming Lender Inexperience

While PACE offers an elegantly simple solution to many obstacles of energy financing, it is in its infancy and few lenders have first-hand experience with it. Existing commercial mortgage lenders, who hold the right to approve any encumbrance added to a mortgaged property, are slow to see any value in consenting to a property assessment that is senior to their loan. And if a commercial mortgage has been already been pooled into a commercial mortgage-backed security (CMBS), a PACE lien would no longer meet the original underwriting criteria.

But David Gabrielson, executive director of PACENow, believes that lender reluctance can be overcome. “We tell lenders that they should look at PACE like any other assessment on the property. For years mortgage lenders have dealt with property tax assessments that may be senior to a mortgage claim,” Gabrielson says. “The PACE assessment is no different, and it may improve the economics of the building.”

For a shopping plaza in Norfolk, CT, PACE financing provided through the state of Connecticut’s Clean Energy Finance and Investment Authority (CEFIA)was the best vehicle to fund an exterior LED lighting retrofit.

“The beauty of this program is that the cost of energy-saving projects can be passed on to the tenants through the tax assessment, but the energy savings that the tenants receive are greater than the increased cost of the assessment,” says building manager Robert Hartt of Hartt Realty Advisors. To ensure that tenants understood the funding, the building owner and manager met with the tenants to explain the capital pass-through via the assessment and the net-positive impact for tenants.

Hartt would not hesitate to use PACE again. “Everyone should look into it and see if you have it in your state,” he says. “If you don’t have it, you need to work on the legislators to get it going.” PageBreak

ON-BILL FINANCING: ON TARGET FOR GROWTH

Like PACE financing, on-bill financing minimizes upfront costs, but rather than spread payments over property tax bills, the latter spreads them over utility bills. Also like PACE, the money saved on utility bills after the energy improvement has been implemented can exceed the loan payment, making cash flow positive from the outset. Many programs require that the energy savings meet or beat the corresponding charge on the utility bill.

Energy savings far into the future can be matched to long on-bill repayment periods, even extending to future building owners and tenants. For the utility, on-bill programs can drive efficiency that helps meet legislative energy targets, manage peak loads, and avoid the cost of new power plants.

States with on-bill financing programs include California, Oregon, Illinois, Wisconsin, Georgia and New York (see map). Other states have pilot or pending programs. Due to varying state regulations and utility structures, the specifics of individual on-bill programs vary widely. They can be structured as loans, tariffs or service agreements.

While on-bill financing (OBF) has been available for years and is the most common on-bill option, a related model called on-bill repayment (OBR) is more recent and has the potential to vastly increase the capital available for energy efficiency. OBF programs are limited to utility or ratepayer funds, but OBR programs tap into a potentially far larger pool of third-party capital. This makes the latter vehicle a possible game changer on the energy efficiency field.

“On-bill financing requires the utility to make the loan, do the underwriting, and typically use rate payer or tax payer capital to do it. That means there is a limited amount of capital available,” says Brad Copithorne, financial policy director for the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF). “The OBR idea is that the utilities just do something they’re already good at, which is collecting bills. The private sector provides the capital, and if it decides this is an attractive market, it may choose to invest billions, not millions, of dollars.”

According to EDF estimates, if an on-bill repayment program in California spurred investment in the range of $3 billion annually, it could create 20,000 jobs while reducing electricity use and emissions. OBR could also improve the credit quality of other vehicles including loans, leases, energy service agreements (ESAs) and power purchase agreements (PPAs). PageBreak

ESCOs: ANTICIPATING GROWTH IN THE

PUBLIC AND PRIVATE SECTORS

Two benefits that ESCOs (Energy Service Companies) can bring to the efficiency table are a turnkey solution for deep energy retrofits and performance contracts that guarantee reduced energy consumption. ESCOs that have met accreditation requirements by the National Association of Energy Service Companies (NAESCO) provide added confidence to building owners.

Performance contracts account for roughly 70% of ESCO revenue, followed by design/build contracting at 15% . According to Don Gilligan, president of NAESCO, guaranteed savings projects typically need to be at least $500,000 to $1 million in scope, a size that only the large ESCOs can accommodate, although smaller ESCOs can do such projects but without a long-term guarantee. Because performance contracts typically establish a historical baseline of energy consumption on which to build the guaranteed savings, they are used for existing buildings rather than new construction. Market penetration of performance contracting is highest in the K-12 school sector.

Some sources predict that the ESCO industry will grow its revenues dramatically over the next seven years by continuing to tap its traditional federal and MUSH (municipalities, universities, schools and hospitals) markets, which account for roughly 85% of revenue.

In recent years ESCO revenues have been concentrated even more heavily in the public sector, due in part to the impact of the economic crisis on commercial building owners. Government mandates to improve efficiency are one driver in the public sector; another is the performance contract’s ability to offer an alternative to the routine public procurement process for capital projects.

ESCOs AND COMMERCIAL BUILDINGS

Because ESCOs tend to deliver large comprehensive projects that have long paybacks of 10–20 years, they often are not a good match for commercial buildings whose owners look for a quick improvement to their net operating income. According to NAESCO data, the payback on school projects averages 12–14 years while on a commercial building it averages only 2.7 years. Another factor is the probability of changes in occupancy or use. The typical school is likely to remain a school but a commercial building might undergo changes in occupancy that complicate the future savings spelled out in a performance contract. The long-term creditworthiness of public entities is also more attractive to lenders.

Nevertheless, Gilligan believes that ESCOs will make new inroads into the commercial market if PACE and on-bill financing take hold and the debt is not accelerated when the building changes hands.

“Building owners are reluctant to encumber their property if it interferes with their ability to sell it,” Gilligan says. He also sees an imminent wave of commercial-building mortgage refinancing that will drive ESCO revenues. “As those buildings are refinanced and possibly repositioned in their markets, it’s a good opportunity for ESCOs to get in there and say, ‘If you’re refinancing, now is a good time to do efficiency improvements.’” PageBreak

MESAs: COURTING INSTITUTIONAL INVESTMENT

The Managed Energy Services Agreement (MESA) is one of the newest financing solutions. Like PACE and on-bill financing, the MESA can allow the building owner to hurdle the barrier of upfront cost but it does so in a very different way.

In a MESA transaction a developer firm and its investment partners take on the roles of financier, owner of the installed energy equipment, and intermediary between the building owner and the utility. The MESA developer pays the building’s energy bills directly to the utility for the length of the agreement. It then charges the building owner a monthly fee equal to the building’s historical energy charges. The monthly fee can be adjusted for actual weather- and occupancy-related variables as they have been written into the MESA agreement. The developer puts up the funds for the capital energy improvement.

As the retrofit is implemented and the building’s utility bill goes down, the developer receives the difference between the actual bill and the fee paid to the owner. At the end of the contract, the building owner typically becomes the owner of the energy equipment. In a MESA deal the developer may manage the contracting and maintenance services as well as the financing.

Resolving Split Inventives

Another benefit of the MESA approach is that it can solve the issue of split incentives between landlord and tenants. If a commercial lease stipulates that the tenants pay for their energy as an operating expense while the landlord pays for the building’s capital improvements, neither has great incentives to pay for an energy retrofit. The MESA can bridge this disconnect if the landlord passes the MESA’s monthly charge to the tenants much like the operating expense of the utility bills.

As a relatively new solution with a limited track record, MESAs have not yet gained wide acceptance in the marketplace. Steve Gossett, Jr., CEO of developer SCIenergy and creator of the MESA structure, believes that is about to change. “A large scale is coming to energy efficiency, the kind of scale associated with institutional investments in oil and gas, infrastructure, and real estate,” he says.

Gossett expects a public announcement soon about a large institutional fund for MESA investments managed by a national bank as the general partner. Qualified institutional investors have already been approached by the general partner. SCIenergy and others will participate as MESA developers who bring possible projects to the fund. Gossett believes that most of the fund’s energy efficiency projects will be in the range of $1–$5 million. However, far larger projects up to $25 million could also be acquired. The fund’s deployment schedule requires the institutions’ capital to be spent within three years.

“This transaction structure allows funds for energy efficiency to be extended as a service model. As a result, firms do not need to put new debt on their balance sheet or worry about mortgage lender covenants or liens,” Gossett says. PageBreak

SMALL BUILDINGS: BIG FINANCING CHALLENGES

Bigger may be better but smaller buildings offer an enormous opportunity for energy efficiency. However, they also pose special challenges for financing and implementation.

Buildings under 50,000 square feet consume 47% of all energy in non-mall commercial buildings. Collectively these small buildings are clearly significant energy users, but individually they lack the economy of scale that can help facilitate energy efficiency in large buildings.

Glenn Schatz, small buildings project manager for the DOE’s Building Technology Office, says that small buildings and small businesses do not attract the big banks because, in the eyes of lenders, smaller businesses are not as creditworthy. They are also less likely to attract energy services contractors. Energy projects for small buildings do not receive the energy modeling and simulation of projects for larger buildings. As a result, energy savings are less certain for small buildings and less appealing to lenders.

DOE is promoting programs aimed at building networks in smaller communities that can work together on efficiency – small business owners, small lenders or lenders who lend to small business, and efficiency suppliers. “There are people who know about efficiency, but sometimes it’s difficult to get them all together,” Schatz says.

Despite the hindrance of scale, small buildings have some characteristics that help them to focus energy projects, according to Realizing the Energy Efficiency of Small Buildings, a report from the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the New Buildings Institute. The majority of consumption in small buildings occurs in only seven building types: food service, “Main Street” or attached multiple-use buildings, strip mall, lodging, retail, office and schools.

Among small building types, food sales/service facilities have the greatest savings potential for energy retrofits, according to the DEEP (Deep Energy Efficiency Potential) index. The index creates a single score from four variables: energy density, EUI, market factor and scale factor.

Grocery stores, restaurants, and other tight-margin businesses with high energy costs can profit the most. For example, small fast-food restaurants have the potential to save 45% of their energy cost and receive a simple rate of return between 28% and 66%. Grocery stores that reduce their energy costs by 10% can increase their profit by 16% and their sales per square foot by $50. Finally, small commercial buildings in business districts are consist of similar building types. That similarity facilitates district-scale solutions that take advantage of shared physical characteristics.

Turnkey Solutions to Match the Needs

While upfront cost is usually considered the greatest obstacle to energy retrofits, that statement can be misleading when applied to small businesses that, regardless of available funding, may not have the human resources to carry through a project. For small owners who must focus on their core business, it is critical to have a turnkey package that includes services to assess the property, facilitate a contractor and arrange financing.

“You can give them 100% of the money yet they put it off and put it off,” says vice president Mahlon Aldridge of Ecology Action, a nonprofit that delivers energy retrofits to small building owners for three California utilities. “They can’t be bothered with all the details. But if you hand large businesses the capital or a way to get cheap financing, they will find ways to do it because they have people dedicated to cost reduction and facility management.”

Aldridge’s advice for small owners: Ask the utility if it has a direct-install, turnkey program. PageBreak

While building owners have little control over the cost of their energy, they have far more control over their consumption. Rising costs for energy increase the value of energy efficiency. There’s no time like the present to capture that value.

These suggestions from energy experts and financial consultants will maximize the savings from an energy retrofit.

- Recognize that you may be able to arrange financing with little or no upfront cost. Your organization has probably budgeted the funds for a retrofit already – they’re hiding on your budget’s line item for energy expenses. A retrofit with financing that produces positive cash flow recovers current energy waste that will otherwise be lost.

- Take advantage of all available financial streams. Start the process by going to your state energy office and www.dsireusa.org to investigate rebates and incentives from utilities and from federal, state and local governments. “You can bundle a utility rebate, maybe some on-bill financing, maybe some PACE funding, maybe some third-party funds, and create a package that pays for an entire project,” says Jack McGowan, president of Energy Control Inc. Be aware of the time period when each stream is available so you can move quickly at the right time to assemble your package.

If you have buildings in various locations with different incentives, look at giving priority to the project that maximizes the funds available. “A lender may be interested in a certain kind of project in this location at a particular time but not a year from now,” says NAESCO president Don Gilligan.

- Don’t overweight interest rates. “Building owners look at interest rates as the litmus test of what is a good deal but that can be wrong,” advises Neil Zobler, founder of Catalyst Financial Group. “Rates are important but owners should not jump at a deal only because of a low interest rate. Terms, timing, lender’s restrictive covenants, and other factors are critical and can seriously detract from a low interest rate offer. Cash flow should be a primary concern when financing energy projects.”

Owners who wait in hopes of getting a lower interest rate may find that the cost of delay is greater than the savings from a better rate. ENERGY STAR’s free tool, the Cash Flow Opportunity Calculator, can compare the impact of interest rates and the cost of delay.

- Look for opportunities to carry an energy project on the back of another capital project. Adding an energy project to a large but unrelated capital improvement project can be an opportunity to leverage funds and acquire financing for little extra effort, according to Getting to “Yes” for Energy Efficiency: A Guide to Developing a Persuasive Business Case for Energy Efficiency in Commercial and Corporate Properties, a report by the Maryland Energy Administration and Catalyst Financial Group, Inc. Moreover, the savings from the energy portion might help pay for the other improvement.

- Use multiple metrics to evaluate energy projects. Simple payback and return on investment are good first-cut tools to evaluate the potential of different energy projects but more information is needed. For example, simple payback cannot account for savings that will continue to accrue beyond the payback point.

A better indicator is lifecycle cost analysis, which evaluates savings over the service life of the equipment. Internal rate of return (IRR) can be used to compare an energy project’s performance with a company’s profit margin and determine which is better. Cash flow analysis and net present value (NPV) also help to compare the return on an energy project to those of other investments.

- Calculate the hidden benefits. Research shows that energy projects deliver an average 11% return beyond the direct savings from reduced consumption, according to Eric Woodroof, founder of Profitable Green Solutions and a board member of the Certified Energy Manager Program of the Association of Energy Engineers.

These hidden savings include longer service life for equipment used less often, avoided capital cost for new equipment, and lower cost for maintenance labor. For example, a control system that turns lights off earlier extends the life of the lamp and the labor to switch it out. By reducing operating expense, efficiency projects can add to the value of a property upon sale.

Chris Olson [email protected] is chief content director of BUILDINGS.

Siemens Building Technologies Division is the sponsor of this special report and its industry survey.

Siemens Building Technologies is a world leader in the market for safe and secure, energy-efficient and environment-friendly buildings and infrastructures. As a technology partner, service provider, system integrator and product vendor, Building Technologies has offerings for safety and security as well as building automation, heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) and energy management.