Most buildings are designed to create a uniform thermal environment that satisfies the majority of occupants. ASHRAE Standard 55 stipulates only 80% of your occupants need to be comfortable. It’s true that you will never be able to make everyone happy or influence personal factors such as clothing or metabolism. But in a building with 1,000 people, are you prepared to handle 200 complaints?

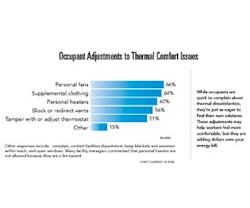

Brushing off thermal dissatisfaction could cost you in the long run. Facility managers or engineers often overcompensate by adjusting thermostats ineffectively, leading to possible energy waste. “When properly recognized and addressed, thermal comfort complaints can result in better productivity and lower energy costs,” says Patrick O’Donnell, managing partner of Enviro Team North America, a firm specializing in indoor environmental quality issues and building diagnostics.

By understanding the four underlying causes of thermal discomfort, you can take an investigative approach and make adjustments that satisfy occupants and your budget.

1) Temperature Wars

Too often, facility managers point to the thermostat, say the temperature is acceptable, and dismiss the occupant’s complaint as a personal preference.

Remember, though, that temperature is actually the combination of two variables. “The operative temperature is the average of the air temperature and the mean radiant temperature of all of the surfaces surrounding you,” explains Peter Alspach, a voting committee member of ASHRAE SSPC 55 on Thermal Comfort and associate principal at Arup, an engineering consulting firm.

You need to investigate sources of radiant heating asymmetry – computers, body heat, lighting, walls, partitions, and windows. This is why the room temperature may appear to be satisfactory but the occupant senses a different temperature in their microenvironment, explains O’Donnell.

These dynamic adjustments in radiant temperature can occur on a daily basis, largely as a byproduct of shifting sunshine and weather conditions.

“The facade is the single biggest component of thermal comfort, albeit a complex one,” says Alspach. “At the perimeter areas, you’ve got a greater range of temperature differences as the external conditions are being mitigated. Interior spaces have a greatly reduced number of variables affecting thermal comfort.”

A worker near a south-facing corner may complain about being too hot in the afternoon but is otherwise fine the rest of the day. Likewise, an employee near a window may be freezing in the winter. As the window leaks 20-degree air, it mixes with the 72-degree air from the HVAC system, effectively lowering your intended temperature.

Be aware that a one-time reading may not fully reveal the extent of the issue, particularly if it’s influenced by a certain event or time of the day. Consider assessing an area’s conditions at multiples times over a series of days.

“A better understanding of the environment can include the placement of temperature-humidity recorders deployed throughout the space over a period of time,” O’Donnell says.

Occupant Feedback

It may feel risky to do, but handing out a basic survey to occupants will help you outline where issues exist. It may be that only one specific area is experiencing discomfort, not the entire facility.

You can also interview individual occupants for further details. Open communication and cooperation validate their concerns and make them more receptive down the road to solutions or behavior modification.

Sample Survey

What kind of symptoms or discomfort are you experiencing?

Are you aware of other people with similar concerns? If so, what are their names and locations?

Yes_______ No________

Are you aware of any factors or conditions that are contributing to your discomfort?

When did your symptoms start?

SOURCE: Adapted from Building Air Quality: A Guide for Building Owners and Facility Managers – EPA and National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

It’s also possible that a direct source of radiant temperature or humidity can be found within your building, such as a freezer area or pool. “You could have conditions where a small server room causes the entire facility to be overcooled 24/7,” explains O’Donnell. “You can resolve the matter by installing a small air conditioning system in the server room.”

2) Air Diffusion

Beyond temperature, air delivery is another key factor. Whether stagnant or too direct, an improper balance of air movement will negatively impact occupants. Problems can arise when:

- Vents are improperly directed at workstations.

- Air registers no longer throw air the intended distance.

- Constant drafts lower the operative temperature.

- Partitions or interior walls block or redirect air movement.

Many times, these issues are the result of modifications made to the space that didn’t account for air delivery. “In these cases, you need either better air balance or air distribution to mitigate these thermal comfort conditions, such as relocating or adding another supply or return register,” recommends O’Donnell.

Door drafts can be difficult to manage because changing your door system – such as upgrading to a revolving door or a double set of entry doors – is rarely an option. It may sound counterintuitive, but you can eliminate thermal dissatisfaction near entrances with simple space heaters.

“For one project, we put in little kick heaters for the receptionists, who were always cold because of drafts from opening doors. But instead of just turning them on, each unit has a 30-minute timer to save energy,” Alspach explains.

For workers who are too warm, a simple oscillating fan can also do the trick if you can’t physically change the location or placement of vents. Facilities managers are often loath to resort to fans or heaters, but if you can satisfy one or two employees, they may be worth the slight increase in energy use.

3) A View with a Draft

Particularly in older buildings, leaky or poorly tinted windows are a significant source of radiant heat and chilly drafts. The cost of replacing windows is substantial, but facilities managers can turn to weather stripping and solar films instead.

“You want windows with the highest light-to-solar-gain ratios,” recommends Alspach. “The higher the ratio, the more light is let in and the more heat gain is blocked out. Use retrofit solar films for glass to block this additional solar radiation. Even single- and double-panel glazing can benefit from modern low-E coatings.”

Personnel Reporting

Have your maintenance staff do a walkthrough of the facility and fill out a personnel log. This will help you reinforce where the complaint area is, bring to light any patterns, and determine if there is a correlation to your mechanical systems.

Sample Log of Activities and

System Operations

Record your observations of mechanical system operation, maintenance activities, and any other information that you think may be helpful in identifying the cause of thermal comfort complaints in this building. Note any other pertinent observations as well (e.g., weather, associated events).

Equipment and activities of particular interest:

Air Handler(s):_____________________________

Exhaust Fan(s):____________________________

Lighting: _________________________________

Drafts:_________________________________

Windows:_________________________________

Other Equipment or Activities:_______________

SOURCE: Adapted from Building Air Quality: A Guide for Building Owners and Facility Managers – EPA and National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

Interior glazing systems are another option, allowing a building to maintain the existing character of its facade or windows.

While shades are a common solution, they may cause more problems than they actually solve. “Top-down shade systems tend to block access to daylight and outdoor views. This interferes with sustainability goals and can lead to lights being run for longer periods of time,” cautions Alspach.

There can also be ownership issues with shades. Particularly in open offices, there may be conflict over which employees have control over adjusting the blinds.

“Use bottom-up shades instead so you block the lower portion of the window,” advises Alspach. “Daylight still comes through the top and will penetrate deeper into the space.”

If drafts are an issue, use thermal cameras to identify leaks and redo weather stripping to block air movement. This is a low-cost option that’s particularly ideal for historical, outdated, or operable windows.

4) HVAC Tweaks

After you’ve pursued obvious fixes, turn a critical eye toward your HVAC system. “HVAC systems are tested, adjusted, balanced, and commissioned when they go in, but modifications and age take their toll – no one’s gone back to make sure the system’s still working like it is supposed to,” Alspach says.

You may find that trunk lines have been changed or broken, or that a vent was turned off during repair work and was never turned back on. “We’ve looked above ceilings and found ducts and air registers and cans that are blowing and aren’t connected to anything,” says O’Donnell.

Use any of these basic tests to evaluate your HVAC system:

- A duct leakage assessment will determine if air is being delivered to the occupants and isn’t bypassing them. This is particularly helpful in a multistory building.

- “Conduct a performance assessment to understand how the air conditioning and heating apparatus actually handles its entering and leaving air conditions,” O’Donnell recommends. “In a cooling climate, you could have staging conditions that don’t allow for proper moisture removal under part-load conditions.”

- Check for mechanical failures of the motors, thermostats, or valves in VAV boxes. Located above the ceiling, it’s easy to forget these systems are there, yet improving them is relatively inexpensive.

- Make sure you have proper balancing dampers and have a technician or engineer adjust them. They can be tricky to successfully fine-tune on your own.

As you run tests, it’s worth your time to have the building’s original plans on hand. You need to establish differences between the as-built and initial conditions.

You could find that windows were upgraded in the past without corresponding adjustments to the HVAC. “The original facility may have had window tinting, but external and internal shading were added when the windows were later replaced,” says O’Donnell. “In the beginning, most of the sensible heat was generated from the lighting, which has since been upgraded. Now your air conditioning is oversized and you’re paying money and getting less humidity control.”

Alspach recalls a recent project for a 1920s steam-heated building. They learned that it still had the original controls – three temperature sensors on one floor that controlled three vertical zones for the entire 14-story building. To remedy the situation, they installed thermostatic radiator control valves on individual radiators on each floor.

Keep in mind that any changes to your HVAC system should be backed up by thorough testing and possibly the guidance of an engineer.

“You need to understand the exhaust systems, the makeup air system, and its relative pressure requirements before making changes,” advises O’Donnell. “You cannot arbitrarily go in without evaluating the environment and shut down the makeup air because you could cause adverse pressure relationships in the building.”

Staying Ahead of Complaints

Thermal comfort is a never-ending battle for facility managers. Remember that it’s imperative to identify the sources of thermal dissatisfaction that are unique to your facility. Only then can you take the steps necessary to address them.

Jennie Morton ([email protected]) is associate editor of BUILDINGS.

About the Author

Jennie Morton

Jennie Morton is a freelance writer specializing in commercial architecture, building engineering, and sustainable design.