Stop Leaks in Their Tracks with a Dependable Air Barrier

Amid the push to make commercial buildings more earth-friendly, one necessary fix is sometimes overlooked – cutting down on hidden heat leaks by adding a durable air barrier to a low slope roof. Up to 40% of a building's energy costs for heating and cooling are wasted by uncontrolled air leakage, which also contributes to condensation, ice damming, poor indoor air quality, and mold, according to the DOE.

What's the Difference?

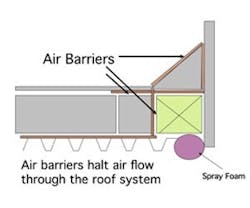

Unlike a vapor retarder, which restricts the flow of water vapor through material by controlling the rate at which moisture diffuses into the building assembly, an air barrier restricts the flow of air, which may be carrying moisture with it. Retrofitting an existing roof system with high R-value insulation but ignoring the air leakage results in little payback – any air leaks must be treated at the source, starting with an infrared detector survey to seek out the leaks and determine the best course of action.

Depending on the roof to wall design and how penetrations have been treated, it may be possible to retrofit the existing envelope system by creating an effective air barrier on the bottom side of the roof deck. Board stock, self-adhering membrane and sprayed-in-place polyurethane foam can all be effective and offer paybacks of five years or so.

An air barrier may also offer more flexibility. Air barriers can be installed anywhere in the roof cross section, but a vapor retarder must be placed on the side of the roof with higher vapor pressure, where the moisture would try to move outward to the cooler side during the winter for a temperate or cold climate.

In a fully-adhered roof membrane system, the membrane itself acts as an air barrier. A contractor would only need to detect and retrofit air flow patterns at roof edges, curbs, pipes and other penetrations to cut down on air leaks. This can be done from the top side (in a roof re-cover, for example), where these penetrations need to be reworked anyway, or from the under deck side if it's readily accessible. (Note that building codes do not permit laying an air barrier directly over lay-in ceiling systems. If the building is pressurized, the barrier film will billow instead of staying put.)

Even the smallest defects in a leaky barrier film will transport more moisture with the leaking air than an average vapor retarder passes by diffusion.

What's Changed?

When built-up roofing was king, a basic vapor retarder consisted of asphalt-saturated felts, which were adhered to the roof deck with hot asphalt, followed by more hot asphalt to embed the roof insulation. Unfortunately, all that asphalt contained a lot of fuel, and when steel roof deck construction was exposed to an interior (under deck) fire, it became a major loss factor.

Nowhere was this more apparent than the 1953 fire at GM's Hydra-Matic transmission plant in Livonia, MI, which initially started as a fire in a drip pan accidentally ignited by a cutting torch. When the plant's hand-held extinguishers ran dry, the fire raged out of control, completely destroyed the 1.5 million square foot facility to the tune of $80 million in damages, and killed or injured 21 people.

After the GM fire, vapor retarders were required to meet fire performance standards when applied directly to a steel roof deck. These days, a vapor retarder must have a flame spread of 25 or less as required by code. The first of these fire rated systems was made of thin PVC film (4 mils or 0.1 mm), which was adhered to the steel deck with cold adhesive, laps sealed with adhesive and then attached to the roof insulation with more adhesive. The fuel content was considerably less than asphalt products, but the permeance (migration of water vapor) was seriously lacking, and the films were hard to work with on a windy day.

Asbestos vapor retarders like Asbestogard and glass-reinforced Kraft retarders laminated together with fire-resistant chlorinated wax offered some improvements, as did single-ply roof membranes, which made it possible to form vapor retarders from plastic films like polyethylene and seal the laps with tape or adhesive. These plastic films had good perm ratings but were extremely difficult to work with and walk on and cumbersome to seal at roof penetrations.

With the advent of high-thermal roof systems, it became practical to first apply a thermal barrier board such as gypsum directly to a steel deck, generally with fasteners, and then to apply vapor retarder films either with hot asphalt, self-adhesion, torch application or another technique. The gypsum thermal barrier also provided a flat surface to simplify lap sealing, something tough to accomplish with a thin plastic film.

Whether a vapor retarder is specified or not, the application of a "nail one, mop one" roof system forms a vapor retarder at the level of the laminating asphalt. It would only be necessary to add a sealant material at roof-to-wall connections and deck penetrations. This is a state-of-the-art advance with roof vapor retarders, but the industry is increasingly turning its attention to air barriers instead.

The Bottom Line

Low slope roofing materials can tolerate some moisture intrusion from the interior during the winter months as long as there is enough solar heating the following summer to drive the moisture back into the interior of the building so the insulation can dry out.

However, the increasing popularity of "cool roofs" that cut down on heat absorption means this may become more of an issue, as the cool roof trend overtakes traditional gravel-surfaced built-up roof systems and reduces the summer solar load. To determine whether to use a vapor retarder to guard against moisture buildup, find your state on this map of the U.S., part of the 1985 ASHRAE report Thermal Performance of the Exterior Envelopes of Buildings III. This tool suggests the maximum interior relative humidity (RH) that can be tolerated without moisture building up from year to year. A higher interior RH requires a vapor retarder.

When air leaks through insulation joints, it can reduce the thermal resistance of the insulation by up to 10%, depending on the width of the joints and other factors. Adding more insulation won't provide a good return on investment unless you can find and eliminate air leaks at the source.

For more information, see Philip D. Dregger's excellent reference, Air Infiltration: The Enemy of Wind Resistance and Condensation Control at: http://www.trsroof.com/Pubs/Dregger/2002-06-dregger.pdf.

RELATED STORIES:

More than Just Roof Leaks

While most roofing professionals naturally focus on the roof system and roof leakage, there's another type of leakage that is at least as important: air infiltration.

The Top 10 Most Common Roof Problems

Discover and understand the problems plaguing low-slope roofs everywhere.

Keeping Up with Changing Roof Requirements

Dick Fricklas, roofing expert, offers an update on the hottest issues in the roofing industry today.

About the Author

Richard L. Fricklas

Richard (Dick) L. Fricklas received a Lifetime Achievement Award and fellowship from RCI in 2014 in recognition of his contributions to educating three generations of roofing professionals. A researcher, author, journalist, and educator, Fricklas retired as technical director emeritus of the Roofing Industry Educational Institute in 1996. He is co-author of The Manual of Low Slope Roofing Systems (now in its fourth edition) and taught roofing seminars at the University of Wisconsin, in addition to helping develop RCI curricula. His honors include the Outstanding Educator Award from RCI, William C. Cullen Award and Walter C. Voss Award from ASTM, the J. A. Piper Award from NRCA, and the James Q. McCawley Award from the MRCA. Dick holds honorary memberships in both ASTM and RCI Inc.