Forging Ahead: Insights from the Inaugural IWBI Healthy Building Policy Summit (Part 2)

[Editor’s note: This is the second installment of a two-part report on the inaugural IWBI Healthy Building Policy Summit held in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 16. Check out the first installment.]

“We all know that this is not a space for the weak or the dilettantes, but it requires long-term commitment. It’s a complicated space, and it’s not easy. I don’t think the challenges and opportunities in the building industry will be solved by Silicon Valley that moves fast and breaks things.”

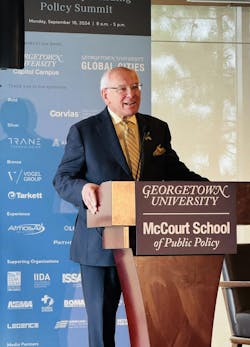

Those were the thoughts from closing plenary speaker Donnel Baird, founder and CEO of BlocPower—and they encapsulated the powerful discussions that preceded it during the afternoon sessions of the inaugural International WELL Building Institute (IWBI) Healthy Building Policy Summit held at the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy in Washington, D.C., for which BUILDINGS served as a media sponsor.

Prior to Baird’s incisive address, the afternoon kicked off with a series of panel discussions and a special address by Rep. Paul D. Tonko, D-NY 20th District, that covered the ways government and the private sector can realize actionable change in advancing building health.

Government in Action

In his opening remarks, Mark Chambers, vice president of Elemental Excelerator, observed that leadership is currently at the forefront of everyone’s minds as the November election is quickly approaching. Government policy around building health is vital, of course, but Chambers reminded attendees of their integral role in getting the industry to where it is today, and ultimately, where it will be in the future.

“I came to the conclusion that policy is not as much about restrictions as it is about momentum. It’s about stockpiling good ideas toward the inevitability of progress,” he said. “We didn’t get here by accident. We’ve been building the momentum and frameworks so you can take advantage of that right now. You are part of that momentum; lean into it. It’s not someone else’s problem to solve.”

The “Government in Action” discussion that followed—moderated by IWBI’s Vice President of Research Whitney Austin Gray, and panelists Katie McGinty, vice president and chief sustainability and external relations officer at Johnson Controls; Dr. Pradeep Prathibha, project manager for the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Department of Energy (DOE), Commercial Buildings; and Brian Gilligan, professional engineer and deputy director for the Office of Federal High Performance Green Buildings, GSA—built upon that premise, demonstrating that we can affect positive change in spite of the complexities facing the industry.

Dr. Prathibha noted in her introductory remarks that the DOE’s mission is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from its building portfolio by 65% by 2035 and by 90% by 2050. “We want to do it so it’s equitable, affordable, and so it promotes resilient communities from climate change, wildfires, etc.”

A perennial challenge facing building professionals in advancing sustainability is the notion that if something is good for the environment, it must be bad for the bottom line, McGinty explained. “We have a variation of that same theme in the indoor air quality space. If it’s good for health, it’s going to be bad for efficiency. We’re trying to shatter some myths,” she added.

Through partnerships with technology providers like Johnson Controls, building owners can realize both human health and cost benefits because technology gives them the ability to quantify results. “With digital platforms we can very clearly measure, monitor, and improve what the outcomes are,” she said. “People think there are tradeoffs, but they’re actually trade-ups!”

Oftentimes, the problem in the public sector is that people are more hesitant to collect data and measure because “if the air quality is bad, are they on the hook for trying to fix it? Are there legal ramifications?” Dr. Prathibha asked.

Gilligan argued that enacting public policy around building health is a step in the right direction, “but until we get our hands around existing buildings operations and maintenance, it’s not going to have the impact you think it’s going to have.” He noted that the GSA Building Links Project utilizes smart buildings technology to collect robust data on operations equipment to a granular level to determine how buildings are performing. “We’ve used it to see what operations and maintenance problems are costing us the most,” and making adjustments accordingly.

Funding the ‘S’ in ESG

Building health plays a critical role in helping investors anchor social sustainability targets, particularly in the context of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) frameworks—a concept explored in depth during the panel discussion titled, “How Health in Buildings is Helping Anchor Social Sustainability.” Moderated by Kelly Worden, vice president of ESG and Investing for Health, IWBI, panelists Chris Pyke, chief innovation officer, GRESB, Chrissa Pagitsas, founder and principal, Pagitsas Advisors, and Anita Chandra, vice president and director, RAND Social and Economic Well-Being and senior policy researcher at RAND, discussed how investors can align their portfolios with the “social” component of ESG, which focuses on factors that impact people and communities as it relates to building health.

Pyke emphasized the growing importance of ESG factors in social sustainability, especially as they relate to investment. He explained that “the goal is to aid investors into risk-adjusted returns” by providing transparency around social factors, enabling better capital allocation. He highlighted the evolution of building performance metrics and their increasing relevance to institutional investors but called for greater expediency in social sustainability concepts: “The actionability on social sustainability concepts needs to accelerate.”

Businesses need to focus on material issues relevant to their sector, according to Pagitsas, who noted that what’s considered material varies across industries, such as pharmaceuticals versus real estate. She also underscored the importance of simplifying the messaging around sustainability and health for different stakeholders: “We have to explain it in ways that those companies will understand. […] It has to follow the K.I.S.S. principle.”

That being said, she added that the financial industry is essentially on time in its understanding of and ability to sell health-related bonds. “Where we are is absolutely normal in the space of getting traditional capital to understand health,” she said. “It’s a specialty. That’s normal in the curve of making new things normal in the capital market.” She added that the industry needs to move forward so that an average investor understands how to trade a health bond with certainty.

Chandra framed health and wellbeing as key to market and social stability, advocating for a broader view of wellbeing beyond traditional health definitions. She stressed that corporate leaders play a significant role in shifting the narrative around health: “Narrative shifts, mindset shifts really do matter,” and she encouraged a more holistic approach to wellbeing that encompasses civil society and business collaboration.

Healthy Schools: A Non-negotiable

The final panel discussion of the day, “A Healthy Schools Imperative: Modernizing and Improving Schools for Health, Learning and Achievement,” in many ways was the most important because it centered on the urgent need to build healthier schools for today’s and tomorrow’s students. Led by moderator and executive director of the 21st Century School Fund, Mary Filardo, the panelists—including Mary Wall, deputy assistant secretary 1 (P-12 Education), Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development for the Department of Education (Dept. of Ed); Andrea Swiatocha, schools portfolio lead for Renew America’s Schools program, U.S. Department of Energy (DOE); Tony Abate, VP and chief technology officer at AtmosAir; and James Macosko, VP, Product Management and Applications at Daikin Applied Americas—unilaterally agreed that the aging infrastructure of our schools demands attention, but that challenges are widespread.

In conversations with school facilities operators, Macosko said many are reluctant to test or monitor the IAQ of their buildings for fear that levels would be unacceptable. “Schools are hamstrung by limited budgets and limited ability to make improvements once a problem has been identified,” he said, adding that there are products, solutions, and technologies available today that can improve the quality of IAQ where ventilation isn’t possible and at a minimal cost.

Wall observed that the industry is in an important moment and that it’s a challenging time for school administrators. In spite of the Dept. of Ed’s historic investment in K-12 schools in recent years, she said it’s grossly insufficient for the existing needs. “We’re looking to elevate the profile of this issue, so that there’s continued insistence and urgency in bringing schools back to pre-pandemic levels of achievement,” she said, adding that the DOE continues to focus on how infrastructure impacts performance in schools.

In terms of modernizing schools, Abate said the ASHRAE 241 standard for control of infectious aerosols to reduce airborne disease transmission in buildings would benefit any environment “and should become the code and not the exception” for schools.

Swiatocha noted that HVAC improvement is the biggest request the DOE receives when it comes to funding building improvements for schools. “The HVAC fundamentally, on a day-to-day basis, impacts children and whether they will stay in school during the day,” she said.

At the end of the day, Wall noted that parents want their children in healthy spaces, which will require sustained funding for IAQ on the local and federal levels.

Following the panel discussion, Rep. Tonko made a special appearance to underscore the importance of air quality in schools and the policies that are being enacted to help advance the cause. “Even though poor indoor air quality is ranked as a top five risk for public health, we don’t have a Clean Air Act for indoor air,” he said.

Earlier this year, Rep. Tonko, along with Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA 1st District), announced the introduction of their Indoor Air Quality and Healthy Schools Act, bipartisan legislation that would protect the public from poor IAQ—especially school children. “Children are more susceptible to the harms of poor indoor air. They spend more time in school buildings than anywhere else,” Rep. Tonko said, adding that studies show that proper indoor air quality improves student performance and test scores. “Children should be a guiding force to making things happen as this indoor act would do.”

Looking Ahead to the Future

The inaugural IWBI Healthy Buildings Summit concluded by emphasized the pressing need for long-term commitments to improving building health, with leaders from government, private sectors, and education advocating for policies that promote sustainability, better indoor air quality, and social equity. As Rep. Tonko emphasized, the future of healthy buildings will rely heavily on regulatory efforts, investment in infrastructure, and community engagement to ensure that health and sustainability go hand in hand in shaping our built environments.